Read this post on the updated SHGAPE Blog website.

By Dr. Gloria-Yvonne Williams

January 11, 2022

This is part of a series of blog posts on women’s history and the long Progressive Era, honoring the legacy of the late Elisabeth Israels Perry. Perry served as SHGAPE President from 1998-2000 and had a long and distinguished career that highlighted women’s political activism in GAPE and in the “long Progressive Era” that stretched into the 1920s and 1930s. This blog series coincides with the July issue of the Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, which includes a roundtable (available to subscribers online) on Perry’s After the Vote: Feminist Politics in La Guardia’s New York (2019). Read the other posts in the series here and find the CFP here.

The Journey

“And so our mothers and grandmothers have, more often than not anonymously, handed on the creative spark, the seed of the flower they themselves never hoped to see. . . .”

~ Alice Walker, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens

In the introduction to her biography Belle Moskowitz: Feminine Politics and the Exercise of Power in the Age of Alfred E. Smith (1992), Elisabeth Perry explains her “initial reason” for searching for extant papers on her subject: “Belle Moskowitz was my paternal grandmother. She died before my parents . . . had even met.”[1] She expounds further upon this fact in The Challenge of Feminist Biography: Writing the Lives of Modern American Women (1992). In this anthology each author explores the craft of “writing the lives of women from a feminist perspective” and shares their “methodological and conceptual tools” and their personal challenges.[2] Perry’s chapter, “Critical Journey: From Belle Moskowitz to Women’s History,” discusses why she decided to write her grandmother’s biography, her research process, and what she gained from the experience. In a similar vein, my master’s thesis is a biography of my maternal grandmother, entitled “Memories: Writing the Life of Mayme Williams Carney” (1992), and chronicles her life history as well as my experiences during the research process.

Cover of Elisabeth Israels Perry’s first book, Belle Moskowitz: Feminine Politics & the Exercise of Power in the Age of Alfred E. Smith (1987)

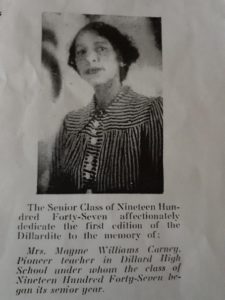

Thus, my first attraction to writing this essay stemmed from the obvious: Perry and I were driven by uncannily similar motivations to write a biography of our respective grandmothers. Like Perry, I had researched the life of a grandmother whom I never met. Both of our grandmothers died suddenly, leaving scant resources, particularly in the form of private papers (such as handwritten or typed letters) regarding their life, meaning that we had to rely upon living family members, our subjects’ acquaintances, and colleagues to gather information. My grandmother, Mayme Carney (1906-1946), was a Black, Presbyterian, Southern high-school teacher of English, Literature, and Drama, and while also a public poet. Belle Moskowitz (1877-1933), Perry’s grandmother, was a White, Jewish, Northern social reformer, and political woman. Both of our subjects lived during the Long Progressive Era. My grandmother was born in North Carolina, three years before Belle Moskowitz became active as a social reformer in New York, in 1909, pushing for the regulation of urban dance halls to create a safe environment for adolescent girls and young women. And when my grandmother attended Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina, from 1923-1927, Moskowitz was well into her second marriage and developing her political career as a close advisor and campaign manager for Alfred E. Smith (1873-1944). By the 1930s, both women were prominent in their own communities. Most importantly, both women were uniquely significant and impacted the lives of many people, yet their existence was invisible and needed to be lifted onto the pages of history.

Writing a historical biography has its challenges, yet because of the subject of our biographies, we both experienced a special set of challenges. I wrote my master’s thesis as a reflexive narrative. In other words, my thesis is based upon my memories of stories handed down to me through the years, including oral histories regarding my grandmother’s life, yet also documented with historical facts and archival sources. Therefore, during my first semester as a doctoral student in history, I was contemplating publishing and decided to ask a female professor to read my master’s thesis. She agreed, and my excitement over what seemed to be her willingness to embrace my work, soon turned to disappointment. When I inquired about her impression, she had decided not to read my thesis once realizing that my memories of stories about my grandmother’s life were a part of the narrative.

Mayme Williams Carney. This photograph and dedication appeared in The Dillardites, 1947, Dillard High School’s first yearbook. DigitalNC, Raleigh, North Carolina.

Perry had a somewhat similar reaction in the early stages of her research: “[M]y first grant proposal to the National Endowment for the Humanities elicited the comment that I seemed to be ‘just writing a book about my grandmother.’” Perry explained further,

When my husband moved to a job at Indiana University, the department newsletter announced that his wife was writing “a history of her family.” Indeed, some people thought I was a genealogist: why else would I be interested in my grandmother? I can smile about these remarks now, but at the time they hurt.[3]

The journey towards writing our biographies developed overtime. When Perry was a teenager, her maternal grandfather mentioned the prospect of writing about her grandmother. In the introduction to her biography, she recounted that conversation:

. . . I recall no one mentioning her to me until one day, when I was about sixteen, my mother’s father, Frank Commanday, said, “When you grow up you must write a book about your Grandma Belle.” Who was she? I asked. “Ask your father,” he replied, and I did. I remember his [my father’s] exact words: “She was Al Smith’s campaign manager, and you can’t write a book about her. No one can because she wasn’t a ‘saver.’ She threw away her papers.”[4]

In contrast, I grew up with an insatiable curiosity about my maternal grandmother Mayme Carney. Some of her extant writings, such as a collection of her typed poems in a handmade binder, and artifacts from her life were kept in the closet of my childhood bedroom inside a large trunk that once belonged to my grandmother. Additionally, I was privileged with my mother’s endless stories about her mother’s life. I also heard stories about my grandmother from my parents’ high school friends from Dillard High School in Goldsboro, North Carolina, where she taught. Many of them knew my grandmother as either their former homeroom teacher or their English teacher. I therefore grew up surrounded by tangible items, from my grandmother’s life, and informal oral histories, which in my mind made her quite real and loved.

Before deciding to research her grandmother’s life, Perry was married with children, a published historian, and a college professor. I similarly was married, a mother, and a graduate student before actively beginning to research my grandmother’s past. What began initially as a task to unearth facts about my grandmother’s life, to fill in the gaps of that curiosity I had grown up with as a child, turned into biographical research when I discovered a unique master’s degree program in Liberal Studies that gave me the creative space to continue my research and write a historical biography of my grandmother for my thesis project. The program had core courses focusing on the planet, the polity, and the self. Having to choose one of those themes for my thesis, I chose the self.

Our respective journeys were rooted in our family experiences. Numerous stories handed down to me by my mother were enormously influential in convincing me to search for answers to questions about my grandmother’s life, which sent me, a novice, on a journey conducting archival research and field interviews. According to Perry, her “excitement began to mount” after her mother mentioned a new book with material on Moskowitz, which became a deciding factor in pursuing her research. But thinking back on the process, Perry recalls “writing about her forced me to explore new research techniques.”[5] Nevertheless, each of our research projects was built upon a quest to uncover and recover our grandmothers’ life history.

Belle Moskowitz. Courtesy of the Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives and World Wide Studio.

Uncovering Evidence in Unexpected Places

Perry’s research process was guided by her ancestral link to her subject, which shaped her research in a significant way. For example, she found archival evidence proving Moskowitz’s political relationship to Albert Smith only after ignoring an archivist’s warning not to waste her time in a collection:

After exhausting the name index, I worked through the topic lists of Smith’s files [at the New York State Library], examining all those on topics I knew would have interested Moskowitz, even if only peripherally. . . . One day I hit a delicious find. I opened a file on water power from Smith’s post-1929 private papers and discovered fifteen letters from Moskowitz to Smith, from the mid-1920s, none of which had anything to do with water power![6]

When she reflected on how her kinship impacted her research experience, Perry states emphatically, “[T]here is no doubt that my personal link to Belle Moskowitz gave me the drive to see the project through, despite its length and difficulty and despite its discouragement I often felt. Somehow, I believed I owed her and her generation its completion.”[7]

During a low point of my archival research, I also found the motivation to continue, from my personal ties to my subject. I had been reading Carl G. Jung’s text Memories, Dreams, Reflections, and came upon the following passage where he reminisces about the significance of his heritage: “I became aware of the fateful links between me and my ancestors. I feel very strongly that I am under the influence of things or questions which were left incomplete and unanswered by my parents and grandparents and more distant ancestors.”[8] Jung’s words confirmed an unspoken belief: I had a responsibility to fulfill my grandmother’s legacy, as an educator, by completing her biography.

Thus, I spent countless hours searching through microfilm from the 1930s and 1940s of the Goldsboro News-Argus, the local newspaper of my grandmother’s hometown, feeling determined, yet without a clue, about what I might find. One day, I stumbled across a small column entitled “Among the Colored,” which appeared towards the end of the newspaper. I was ecstatic! And although that column was a stark reminder of the racial social structure in the 1930s, it provided me with a window into my grandmother’s activities in her public and private spheres. For example, there was an announcement of her making a record with her students in which she recited one of her poems, and another piece about her family traveling out of town in 1931 to attend the funeral of Mayme’s maternal grandmother—my great-great grandmother.

Through the discovery of that column, I also learned more about my grandmother’s significant presence and influence in Goldsboro. My grandmother taught at Dillard High School for sixteen years, and founded the school newspaper. In October 1939, the following appeared in the “Among the Colored” column: “This column will be edited in the future by the Dillard Hi News staff. . . . Any information or news for publication should be sent to the Journalism class or to Mrs. Carney at room 10 the day before the evening of publication.”[9] Obviously, she had editorial control over the community’s news, therefore working across race.

Being related to the subject of one’s biography can also be a catalyst for making contacts in the field, such as providing access to oral testimonies, which can be helpful in sketching a fuller portrait of a woman’s life history. As the granddaughter of Belle Moskowitz, Perry gained an “entrée into places,” meeting influential people who had a connection to her grandmother. “My kinship with Moskowitz,” she explains, “created a personal dimension to my subject that not all biographers will share with theirs.”[10] That advantage gave her access to Aline MacMahon (1899-1991), an actress, who Perry referred to as her “best living source.” MacMahon and “Belle traveled to California in 1932.” During that trip, MacMahon wrote letters to her husband. According to Perry, “MacMahon had kept those letters, parts of which she read into my tape recorder,” and the “written record jogged her memory of poignant details about Belle’s last days.”[11]

Initially with the help of my parents, I tracked down and interviewed some of my grandmother’s friends and colleagues; many of them I continued to contact on my own, including an interview of my estranged grandfather, Mayme’s husband. I was granted telephone interviews, received several of my questionnaires back and to my surprise completed. Eventually, I gathered valuable material that assisted in shaping a narrative of my grandmother’s teaching career, and uncovered examples of her work as a public poet. For example, in 1991, as a result of my fieldwork, I recovered my grandmother’s poem “After-thoughts,” written in December 1939. One of her former colleagues gladly handed over a copy that my grandmother had given to her, explaining that it was one of Mayme’s favorite poems, and that “She could compose a poem for any occasion and frequently did.”[12]

Reading “After-thoughts,” I heard my grandmother’s passion for teaching. She expressed a noble duty for her profession, reflecting upon what she deemed to be her social responsibility to shape the mind and character of her students. She wrote that she would “teach them to be pioneers/Who blaze a lonesome trail,” “teach them to be statesmen/Who for the right are sent,” and “teach them to be soldiers/Who never carry guns.” She firmly acknowledged, “this is my realm/This classroom is my throne/In it I’ll reign with justice/I’ll make each child my own.”[13]

The personal connection to our subjects not only motivated our research but also gave us access to otherwise hidden sources.

The Relationship Between Biographer and Subject

“[In] the realm of research methodology . . . the relationship of biographer to subject arises out of the narrative.”[14]

~ Craig Kridel, Writing Educational Biography

In the end, writing a biography became a personal journey for both of us. For example, in “Critical Journey,” Perry reveals in the closing remarks of her essay, “I had never felt close to my father or known or understood him well. Learning about the early death of his own father and the frequent absences of his mother helped me to understand him better. This knowledge has given me a certain peace about our troubled relationship.”[15] She also discloses in that essay the impact of her overall experience: “Writing the life of Belle Moskowitz took me on a long journey. Because she was my paternal grandmother, learning about her meant learning about a part of my family I never knew, and thus more about myself.”[16]

In my grandmother’s biography, I openly embraced two narratives, Mayme’s and my own, and characterized my overall experience in a tone that echoed Perry’s:

I have come to know more about myself and my relationship with my mother and my own cultural heritage. I have been able to locate my maternal roots back to the year [of] 1843.

In other words, in trying to define Mayme’s Afra-American experience, I have come to understand a significant part of my own.[17]

In their introduction, the editors of The Challenge of Feminist Biography (1992) proclaimed, “Our essays . . . are individual ‘autobiographies’ of our biographies and of ourselves.”[18] Reflecting on the completion of her biography of a twentieth-century labor activist, historian Dee Garrison shares her innermost thoughts: “In many ways, she shaped my life as thoroughly as I shaped hers.” Unlike our reasons for writing a biography, Garrison selected the subject of her topic because of her interest in writing about radical women.[19] Yet Garrison experienced an intimacy with her subject, characterizing it as an interrelationship, and her reflections read more like an autobiography. As Susan Ware, a historian and biographer, clarifies, “[B]ehind every biography lies autobiography,” a concept that is not new to the craft. It’s “the spark that draws a biographer to a subject in the first place,” Ware explains, “and the interaction that unfolds as the project moves forward.”[20] Having an ancestral link to your subject seems to make a difference in writing biography, but is not a requirement for developing a relationship with your subject. That literary relationship develops inherently, as part of the craft.

Writing a biography of a woman’s life also shaped our interests in women’s history. Perry, who started out a scholar of French history, admits as “a historian who happens to be a woman, writing . . . [Belle’s] life led me to confront both her and my own relationship with the women’s movement. That last experience took me into women’s history, permanently changing the personal and professional direction of my life.” As a historian of women’s history, Perry’s scholarship was instrumental in illustrating how Progressive Era women “[a]lthough excluded from the power elites . . . found creative, if unrecorded, ways to exercise power.”[21]

In terms of my own transition into the field of Women’s History, I took Women’s Studies courses for a few years as an adult student prior to studying for my master’s. Later, when writing Mayme’s biography, I delved deeper into Black women’s history and literature. I then pursued a traditional doctorate in history, but with an interdisciplinary focus I worked across departments and selected the field of Gender and Women’s Studies as my major concentration. Finally, I felt that I had found my calling. Tracing the life history of our respective grandmothers led us both down the path of becoming historians of women’s history.

Dr. Gloria-Yvonne Williams is an independent scholar and an adjunct college professor, specializing in History, Gender & Women’s Studies. She is redeveloping her dissertation for publication, which is entitled “‘Appreciate that You’re Rising’: Mary McLeod Bethune, Race Woman Leader & the New Deal.” Her professional webpage is http://www.independent.academia.edu/gywilliams.

Cover Image: New York State Capitol, looking north, Albany, New York, ca. 1910-1918. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

[1] Elisabeth Israels Perry, Belle Moskowitz: Feminine Politics and the Exercise of Power in the Age of Alfred E. Smith (New York: Routledge, 1992), x.

[2] Sara Alpern, et al., The Challenge of Feminist Biography: Writing the Lives of Modern American Women, (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1992), 3.

[3] Perry, “Critical Journey,” in The Challenge of Feminist Biography, 95.

[4] Perry, Belle Moskowitz, x.

[5] Perry, “Critical Journey,” 82; 81.

[6] Ibid., 85-86.

[7] Ibid., 95.

[8] Carl G. Jung, Memories, Dreams, and Reflections (New York: Vintage Books, 1989), 233.

[9] Gloria Yvonne Williams-McCowan, “Memories: Writing the Life of Mayme Williams Carney,” (M.A. thesis, Loyola University Chicago, 1992), 68.

[10] Perry, “Critical Journey,” 94.

[11] Ibid., 88.

[12] Williams-McCowan, 74n13.

[13] Ibid., 73-74.

[14] Craig Kridel, “Part Two: Methodological Issues and Biographical Research” in Writing Educational Biography: Explorations in Qualitative Research, ed. Craig Kridel (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1998), 77.

[15] Perry, “Critical Journey,” 95.

[16] Ibid., 81.

[17] Williams-McCowan, 101.

[18] Alpern et al., “Introduction,” 3.

[19] Dee Garrison, “Two Roads Taken: Writing the Biography of Mary Heaton Vorse” in The Challenge of Feminist Biography, 70.

[20] Susan Ware, “Writing Women’s Lives: One Historian’s Perspective,” Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 40, no. 3 (2010): 426.

[21] Perry, “Critical Journey,” 81; Perry, Belle Moskowitz, xiii.

The post Writing a Woman’s Life, A Personal Journey appeared first on SHGAPE.